|

[Table of Contents with links follows editorial]

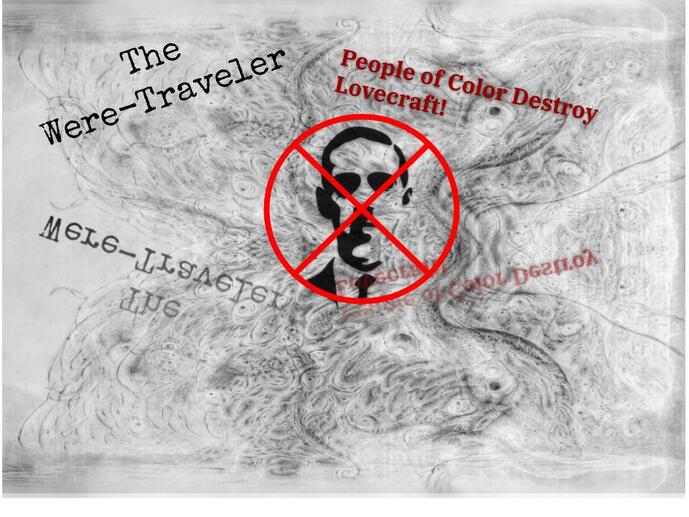

Editorial: Dismantling the Monsters (Especially the Ones in Human Form) This is an issue of timeliness. All that has been going on in our world, all the hate that we still have to deal with, and witness...the overbearing struggle of the human family who have different levels of melatonin in their skin than others…the absurdity of it all. Timely because of the struggles in our country for equality, for sure, and...I saw an ad for a new TV show that kind of mirrors this issue: Lovecraft Country. It’s about the nightmare of people of color and monsters, and some of the monsters are not human, but the most inhuman monsters are. Lovecraft was no humanitarian. He seemed to love his monsters more than he loved other people, especially people of color, as is evident in all of his work. I invited authors to write Lovecraftian tales told from the marginalized perspective. I got some good responses. In one, a wise eternal witnesses righteous vengeance. Lovecraft brings a “friend’ to a Chinese restaurant. An Old One Argues for His Taboo Love. An odd piecing together of the Innsmouth story, stitched together from the fragments of individual reports. A coffee shop brings two people together. Spoiled rich kids go raising hell in the wrong town. There’s lots to love here. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I did. The Stories: The Colour out of Space: The Quietus, by Michelle Mellon (flash) Starcrossed, by Gregg Chamberlain (microfic) THE INNSMOUTH LEGACY (An Oral History, 1962), by Jack Lothian (flash) Noodles, by Michael Anthony Dioguardi (flash) When Starbucks Came to Innsmouth, V. A. Vazquez (flash) Cthulhu Tentacles Are Delicious, by Jo Wu (flash) The Incident at Chicxulub, by Pedro Iniguez (flash) The Shade at Aseneith, by JD DeLuzio (flash) Editor's Picks: The Colour out of Space: The Quietus, by Michelle Mellon THE INNSMOUTH LEGACY (An Oral History, 1962), by Jack Lothian Starcrossed, by Gregg Chamberlain

0 Comments

No one was around when the cracks first appeared. No one was around when they turned into probing tendrils. And no one was around when the wall surrendered and the waters it held rushed forth to cleanse the townspeople of their hubris in trying to contain its power. Officials debated repairs to the dam, while one person watched over the valley whose secrets had been drowned in tears for nearly two centuries. She watched as grey trees and grasses, inexplicably brittle after their submersion, reemerged like a blight in one swath of the newly revealed countryside. And when surveyors and intrepid hikers began reporting an odd whispering wind and impossibly luminescent flora bordering the grey, she stopped watching and closed her door and windows and waited. It didn’t take long before more strange things began happening. There was talk, but the words only stirred up motes of fairy tales best forgotten. There were pleas, but no one wanted to explore the desolate valley to find missing people or unwanted answers. Instead, scholars began digging through newspaper and Miskatonic University archives. What they didn’t find was the truth. Nearly 75 years before emancipation, Massachusetts reported no slaves in the state. But everyone knew they were there, if not in name than in deed. In the valley, black men and women and children who had survived the horrors of formal bondage lived on compounds promising them a bridge to a new life. Instead, they found they had taken the half-step up from slavery to indentured servitude. Most of those people fled Essex County as soon as they could. The others drifted to the edges of local memory. None of them returned to the valley proper. And none of the migrants who approached the valley would stay. They had known much darkness in their lives and could feel the great sorrow of the place. A half-century later, the valley was flooded, and its legacy submerged. But the land did not forget the terrors it had previously hosted. And it certainly did not forgive. And so it was that a man with buried sorrows now entered the valley. He was one of the researchers, and he’d read ancient reports of a farmer who found meteorites with a strange substance inside that seemed to spark a series of tragedies. The scholar considered himself open-minded but did not believe in the inexplicable. Whatever had happened to the farmer Nahum and his family nearly 200 years earlier, and whatever was happening now, must have an explanation. He set a course for the former farmland. Pragmatic as he was, as he approached the area in question, he couldn’t help but be enchanted by the contrast of the grey foliage and the glowing otherworldly plant-like forms beside it. Looking further, he saw the broken lip of a rather large well, and what may have been a farmhouse foundation a short distance away. He moved forward, stepping gingerly over the waving plants and ducking under clutching vines until he reached the well. When the toe of his boot struck the decrepit stone, the valley went still. There was no whispering wind or dancing plants or scurrying animals or any other indication of life around him. But there was something in the well. He could hear it move. A massive slithering, like hardened flesh rubbing over rough rock. He could feel it reaching toward him, doubling upon itself to climb higher and higher from the depths. As if in a dream he peered over the edge into the abyss, but at first could only see shadows shifting from one side of the shaft to the other. Then he saw the first hint of pebbly tissue, like sandpaper skin fused to rock. One moment it curled upward like an impossibly graceful and weightless cloud. The next moment it crawled the walls like a ghastly husky shuffling spider. He could see no distinction between parts. It seemed to be one pulsating body that smelled of something old and ugly and intentional. As he continued to watch, the entity changed from a murky charcoal to a swirl of darting colors. They matched the plants on the periphery of the farm, and he realized the chanting wind had returned and the thing swelling up the well was thrumming to its beat. The lights under its skin were brighter and faster and he could start to see more clearly that the creature was shaping itself into a multi-limbed beast most akin to an octopus. Then it opened its eyes. They were everywhere. The lumps and bumps he’d taken for imperfections across its surface stared back at him now in an infinite array of colors. He leaned further into the well because they beckoned, welcomed, commanded. Just then the thing’s mouth opened, and he saw how impossibly large it really was. On the outside, it filled the full width of the well. But inside was like looking into infinity, down beyond the confines of the well and through the darkness of the earth out the other side to the vast vacuum of space. As he imagined himself falling past the regiment of jagged teeth, bouncing against razor-sharp edges until he was a tenderized piece of flotsam in the flow of the universe, he was suddenly blind. Small warm hands covered his eyes and, attached to strong arms somewhere behind him, pulled him back from the precipice. When the hands fell away, he turned to see a woman about his height, cropped white hair contrasting sharply with her ebony skin. She was of an indeterminate age but when she spoke her voice carried the gravitas of eternity. “You’ve come to find answers,” she said. “But just like the others, you’re asking the wrong questions. Do you know why this land looks this way? Feels this way? Acts this way?” He shook his head. “Because it holds the weight of all the pain and blood and sorrow of our people. The cruel lashings, the cowardly lynchings, the turning of a deliberate blind eye and deaf ear to the misery of those who were first enslaved and then freed into a new form of bondage.” He was mesmerized by her words and tone. And the way the ground heaved with sighs and the song of the surrounding vegetation turned to moans and screams in sympathetic chorus with the story. Underneath it all, however, he could hear a clacking sound. When he looked toward the old foundation, he saw bundles of bare bones scuttling from corner to corner. “All that agony soaked into the soil here,” she continued, “And when the soil couldn’t hold it anymore, it gathered itself together. Into the well,” she waved her arm in that direction. “Into the stones on this land.” “The meteorites Nahum found?” he asked. The woman chuckled. “That poor man and his family. Poking at things they didn’t understand until those things poked back. You know his name means ‘prophet?’ Yet he did not foresee this fate.” She shook her head. “Those rocks didn’t come from beyond the stars. They came from the beyond,” she said. “And the bright places inside those so-called meteorites? The ones that match the colors of their plant kin? Those are the souls of all the brutalized slaves and their offspring.” “How do you know all of this?” he asked. “It happened centuries ago.” She smiled, and it was like catching a glimpse into the book of all answers for all things. “I am the Original Mother,” she said. “And though I do not play favorites among my children, it is time for a long overdue reckoning.” As he looked around, he could see the strange phenomenon spreading across the rest of the valley. The glowing plants drew life in, the grey blight snuffed it out. The bones behind him were racing from foundation corner to corner, clattering out an ominous rhythm. Yet it wasn’t until he heard the moist slap of a tentacle limb hit the outside of the well rim that he ran. “Welcome back, my loves,” the woman cooed as she began sauntering away in the footsteps of the departed scholar. She was not there to direct or guide the vengeance to come. In this valley of the lost, one had to find one’s own way. Soon the grey grasslands seemed invisible under the setting sun and the shrouded moon. The wind hummed an aged dirge. The glowing plants seemed dull in comparison to the sparkling creature that continued to ooze from the well. It was like a nightmare sideshow act made real; the undulating creature spreading slowly across the countryside, seeking reparation, accompanied by the rattle of ancient bones in search of playmates. At such a pace it was hours before the first screaming started, yet the depth of that suffering foretold much more to come. And while others peered from their homes to see if this unknown destruction was coming their way, the old woman closed her door and windows and waited. I have been published in nearly two dozen speculative fiction anthologies and magazines and my first story collection, Down by the Sea and Other Tales of Dark Destiny, was published in April 2018. I am currently completing work on my second collection. ~ Michelle Mellon “Starcrossed: was first previously published on the FunDead blogsite, February 24 2017. “Absolutely not!” roared Yob-Soloth. “I forbid it!” Ten eyes swivelled on their stalks to glare down at the object of the Elder God’s wrath. “I don’t care!” screeched Yag-Soloth. “He summoned me. I answered.” A dreamy look spread across the Elder Godling’s quivering eyes. “We bonded. It was wonderful. We’re soulmates!” “You’re WHAT?” Yob-Soloth raised his squamous body to its full towering height. “No spawn of mine is going to conjugate with a…HUMAN! Go to your plane, and don’t manifest until I say so! Not for an aeon at least!” “I HATE YOU!” Yag-Soloth shrieked before vanishing. “My own sprog consorting with a human!” moaned Yob-Soloth, pseudopods flailing against the aether. “Oh, the shame of it. How will I ever face the Nigguraths and Haggoths at the next conflagration?” The Elder God paused, eyes flaming bright at a sudden thought. “Unless I put a stop to this right now before anyone else finds out. Yes! I’ll track down this human defiler of my offspring and obliviate him! There’s no other way! Otherwise I’ll be shunned in all the infernal circles that matter. Never to appear in the pantheon again. I can already hear that oh-so-superior-I-Rule-for-All-Eternity Cthulhu, giggling through his tentacles in his sleep in R’lyeh.” Yob-Soloth waved a pseudopod in a complicated eldritch pattern. “Pray to whatever gods will listen, human,” he rumbled. “I’ll teach you to bond with my spawn!” The Elder God vanished. Silence reigned in the netherverse. Save for a faint tittering giggle. Gregg Chamberlain is a community newspaper reporter, living in rural Ontario, Canada, with his missus, Anne, and their two cats, who may or may not be from Ulthar but if they are, they're not telling their humans. Gregg has about five dozen short-fiction credits in speculative fiction, ranging from microfic to novelette in venues like Daily Science Fiction, Apex, Mythic, Nothing Sacred, Weirdbook, and other magazines, and various original anthologies. ELSPETH MARSH I read a lot about the oceans, the sea. Do you know there are over two hundred thousand species under the water? And over two million more that remain a mystery? I think that’s beautiful. The idea of a great, deep unknown, beneath those waves. ANDREW McCORMACK (Deputy Head of Public Relations, FBI) Innsmouth is a matter of public record. During the February 1928 operation there, agents learned of a severe health hazard that potentially endangered the public. A decision was made to evacuate and contain. Those involved were commended for their swift action in protecting the American people. AMY ANDERSEN (Reporter, Essex County Enquirer, 1926-30) Yes, I heard the news about Elspeth. (long pause) At the time, I was twenty-six, working as a reporter for the Enquirer. I was ambitious. Didn’t exactly have an eye on a Pulitzer but didn’t plan on spending my life in Massachusetts. There were mutterings about Innsmouth from some law enforcement contacts. At first, it seemed like standard Bureau of Prohibition remit—shutting down bootleggers, lines of supply—-which made the decision to kick it upstairs to the Department of Justice something of an anomaly. Journalists are like rabbits. Something’s in the wind, our ears start twitching. DANIEL KEYES (Editor, Essex County Enquirer, 1920 - 1941) You’re asking me about a story that happened almost thirty-five years ago. I can’t even remember where I put the TV remote this morning. AMY ANDERSEN There were statements from witnesses who’d seen distant fires in Innsmouth, heard what sounded like explosions. Others up the Manuxet River swore they'd spotted sea vessels firing torpedoes into the bay. Nothing could be proven. And then I met Elspeth Marsh. ELSPETH MARSH I was ten years old. A lot of my memories from that time are scattered. There was the raid—fires burning across town, screams and smoke. Men in masks, guns, townsfolk grabbed from homes, marched to waiting vehicles. I tried to hold onto my mother’s hand but lost her in the confusion. I dragged myself into the crawl space under one of the houses by the bay. Stayed there all night, terrified, curled in a ball, dirt in my mouth. I didn’t know what we had done that was so wrong, that made them hate us so. I didn't have a plan. I wasn't brave or strong. I just knew I wouldn't let them take me. AMY ANDERSEN Elspeth was found walking a country lane a few days later by Hector and Eliza North, an elderly couple who had a farm just outside Ipswich. They knew she was an Innsmouth girl from the look of her. I think if she'd been an adult they wouldn't have taken her in, they weren't what you'd call progressive. They trusted the police even less though. I suppose I was known as a sympathetic ear, I'd written a number of local interest stories, and they felt they could trust me. ELSPETH MARSH Amy was like someone from the movies. Long, auburn hair. Sparkling green eyes. She spoke fast and had a big smile. I liked her instantly. AMY ANDERSEN You still hear the expression around those parts. ‘The Innsmouth Look.’ Large eyes, wattling around the neck, a mouth that seems to droop, a peculiar coloring of the skin. Ridiculous rumors about their ancestry, even about what they turned into when they got older. It was the first time I'd seen the look for myself through, and it did take me a little off-guard. But I knew to smile, pretend that there was nothing strange. She was still a child, even if she was different. ELSPETH MARSH I told her everything I could remember from that night. I started crying. I was scared; I missed my parents, my family, my friends. She gave me her handkerchief, told me to keep it. That meant a lot. AMY ANDERSEN It wasn’t an act of kindness, letting her keep it... (long pause) I just... I just didn’t want it back. God, we’re terrible people. Judging others just because they're different. In many ways, I was worse, because I'd act like I was better than that. Her story though…it was incredible. Filled in so many blanks, connected so many pieces. The more I looked, the more threads started to tie into it. A colleague had told me something strange a few weeks before, about how the military Regional Confinement Facility near Colorado Springs had been emptied of prisoners. All of them transferred, no reason given beyond ‘general maintenance. And then I discovered the facility had handed jurisdiction over to the Bureau, which was unheard of. We're talking about the mass deportation and imprisonment of American citizens. LLOYD BOLLAND (Guard, Fort Carson Regional Facility, Colorado, 1921-1928) They brought new staff in. They were erecting ‘temporary accommodation’ in what was the exercise hall. These things were like giant iron cages. I asked one guy what they were for, and he said: “For the children.” I remember laughing, thinking he was joking. After that, most of us got transferred to the facility in Georgia, and I didn’t think much more about it. AMY ANDERSEN I went to my editor Daniel with what I had. I knew it was big. The US government taking families, children, locking them in military detention centers. They practically raised a town to the ground. All because these people weren't, well… They weren’t like us. Daniel said he wanted to meet with Elspeth. If we were going to do this, then we’d have to do it right. I gave him the address of the Norths. Then the story got shut-down. DANIEL KEYES (Editor, Essex County Enquirer, 1920 - 1941) As I said, I’ve no real recollection of any of this. No doubt, there was a lack of evidence to support the claims. We’re a newspaper. We deal with hard facts, not fanciful conjecture. I do remember Ms. Andersen reacted strongly to the decision not to print. Ultimately I had to let her go as a result, which was unfortunate. There was no government interference or pressure. The implication is an insult. This is all history, maybe best forgotten. ELSPETH MARSH They knocked on the door, two men in suits. Mr. and Mrs. North tried to stop them, but there were more men outside. They weren’t rough with me. One of them asked me if I was hungry, needed something to eat. I'd never been in a car before. It was a long drive to Colorado. AMY ANDERSEN I couldn't get hired anywhere. I tried to follow up on the story though, to gain access to the facility in Colorado. I tried to keep going. One morning, I was in a coffee shop, writing up notes. A man sat down across from me. He said he wasn’t with the agency, but G-men have a certain look. He told me if I didn’t stop, there was a place in Colorado for me too. He was very matter-of-fact, like he was discussing the weather. I was broke, unemployed… I just gave up the fight. It’s terrible, but that’s the truth. I gave up. I’d seen them once, maybe fifty people in these drab uniforms, being walked around the yard like animals. I thought that could be me if I kept going this way. I never got to say sorry to Elspeth. But I am. For everything. ELSPETH MARSH These words I’m writing might never see the light of day. I know how that feels. I’m forty-four now. I haven’t seen the ocean since I was a child. Sometimes at night, when the others have settled, and the room is quiet, I can almost see the black waves rolling across the shore and the glimmer of distant lights below. Even this far from home, I still feel the whispering call of the deep. We don’t live long, my people. I have a few years left, at best. I plan to make a run for it. There are guards, men with guns. They don’t despise us, not in the way I thought they did. They fear us. What we are. What we become. I hope the world will change, and one day we won't lock away people, children, in cages, just because they're different. Because of a skin. Because of a look. Either way, I won't be here to see that. I'm going to finish writing this, and get out, anyway I can. Maybe I'm not far from here, in some ditch, a story come to a violent, sudden end. Or perhaps soon I will finally be home, on the cobbled sea-washed streets of Innsmouth, rushing down the lanes that lead to the shore. I'll let the water rise around me, lift me up, carry me under. Do you know there are over two hundred thousand species under the water? And over two million more that remain a mystery..? I really do think that’s beautiful. In my day job I was work as a screenwriter and have been showrunner on the HBO Cinemax show Strike Back for the past three seasons. My short fiction has appeared in a number of publications, including Helios Magazine Quarterly, Hinnom Magazine, the Necronomicon Memorial Book, The New Flesh: A Literary Tribute to David Cronenberg, and Ellen Datlow's 'Best Horror of the Year Volume 12'. My graphic novel ‘Tomorrow,’ illustrated by Garry Mac, was nominated for a 2018 British Fantasy Award. ~Jack Lothian “Are you sure that’s him?” Li peaked over her knuckles from behind the shelf. “Positive.” Wu’s head hovered above her. “I didn’t think he was that tall—” “Well the only photo I’ve ever seen of him was on the back of that book you had.” Wu stumbled above Li, knocking her over in the process. “You buffoon! Watch it!” Wu helped her up and they turned to each other. “You go! I’m too nervous!” Li said, clutching her hands above her chest. “No way! I don’t even know why he’s here?” “Hungry, I guess. The guy likes Chinese food, who doesn’t?” Wu arched his eyebrows and folded his arms across his chest. “You’d think he’d stay clear of places like this. We’re a hole-in-the-wall for Christ’s sake!” “Fine!” Li forced her fists towards the ground. “I’ll do it!” Wu tip-toed back from behind the counter, continuing to spy on the mysterious gentleman seated at the table near the window. As Li shuffled past the counter, she grabbed a menu and approached the man from behind. Tapping her fingers against its spine, she blinked and forced a smile. “Huanying! Welcome, uh—here’s our menu.” Li’s trembling fingers gave out from beneath the menu, dropping it on to the table. The man’s stare cut through Li and boiled her insides with a mixture of fear and frustration. “Our special for today is wonton soup, succulent po—” “Noodles” He said stoically. Li felt a warming sensation on her cheeks and imagined them cherry-red—flush with anxiety. “N-N-Noodles?” He lowered his head and picked up the newspaper next to him. Li remained on the side of the table, pen and paper in hand, waiting to see if the man would order anything else. After several seconds of silent reverence, she turned toward the kitchen and fled to the store room where Wu stood, watching the man from behind the heating rack. Li collapsed next to him. Panting, she reached for the book shelf behind the work desk. Wu scurried alongside her. “So! What happened! Did he call you something! Did he even order! Li!” Li scrambled through piles of books, ignoring Wu’s questions. She located what she was searching for and snatched it off the shelf. Its spine flaked the letters: LOVECRAFT—DAGON. She flipped it in her hands and gazed at the portrait on the back cover. Sneaking behind the storage rack, she held the book so it was level with the man’s frame. She bit her fingers and turned towards Wu. “It’s him! And he wants noodles! Just noodles!” Wu spun away from the counter and emptied a container of noodles onto the saucepan. The sizzling of the fryer interrupted the restaurant’s silence as she continued comparing the two faces. Wu muttered to himself while working the dish beneath him. “H. P. Lovesshmaft...asshole...dickhole...piece of…” “Man, how I wish we could just poison his food.” Li whispered. “Same,” Wu shimmied the noodles onto a plate and cocked his head to the side. “What’s up? Let me guess, you want me to bring it out too?” Li watched her brother’s body language. Wu didn’t reply; he was seemingly entranced by the oily pile on the plate before him. “Nothing…I mean, no! Yeah, I thought I—I thought I saw something, like the noodles were watching me.” Li raised her eyebrows and took the dish from Wu. “You’re losing it. Tell Mom you want morning shifts before you start talking to more food—weirdo.” Li approached Lovecraft’s table and placed the dish before him. He folded the paper and picked up his fork, digging into the noodle pile. From the side of the table, she stepped back and sighed, glancing once more in his direction before escaping behind the counter. # Beneath her feet, the floor tiles peeled upwards and flashed in chromatic shades. Their contours deformed and enlarged into clusters of black cubes that aligned and melted into the darkness. Li’s hands wrinkled, her tongue stuck to her lips, and her cheeks rubbed against air that felt like sand-paper. She fell towards the counter and lifted her head. From Lovecraft’s table oozed a snot-colored stream. Its apex nearly tickled the ceiling; Lovecraft struggled in the mess. The counter rumbled underneath Li’s hands as she writhed about, shouting desperately for Wu. She twisted her head back to the kitchen, only to witness its descent into a murky void. A sinister wind ambushed Li’s chest, forcing her to grip the counter and wail in terror. Pulsing lights protruded from the mess and illuminated the perimeter of the room followed by guttural, horrid shrieks that accompanied the alien light—now a ferocious spiral of cosmic gusts. The noodles deified before Li. Their appendages burst outward in a frenzy of tentacles, gripping Lovecraft by the shoulders and tearing away at his center. Blood spurted from his dilapidated corpse like a loose fire-hydrant, pumping splashes of his innards to stream down Li’s face and into her mouth. She coughed through the membrane of blood collected on her lips and screamed, “Nyarlathotep! The God! Nyarlathotep—Please! No!” # Lovecraft turned around in his seat. He stared at Li while she screamed on top of the counter, her eyes gazing off into her self-created apparition. Wu scampered out of the kitchen and threw his hands around her shoulders, attempting to shake her from the nightmarish stupor. “The noodles...there was...I saw—” Li whimpered. “Would you get a grip! And you said I was losing it.” Wu peaked over Li’s shoulder at Lovecraft, who sat quietly observing the commotion. “I think he’s done. Get it together! Collect his plate! Put you on morning shift—crazy…” Her stomach churned with each passing step. Pulling alongside his table, she bowed and forced her best smile again. “We apologize for any inconvenience.” He hardly ate; the pile was mostly intact. She passed the counter and stood before the bin. As her foot pushed down to open the lid, she caught a glimpse of something moving in the noodle pile. She gawked at the ghastly site before her; her eyes met a stray eye—narrow and crusted with black scales. The eye blinked. Li lost her breath and felt the plate slip from her hands. Mike teaches and writes in upstate New York. His work has been published multiple times by 365 Tomorrows and will be featured in upcoming issues of Close 2 to the Bone, Dark Dossier, Sirens Call eZine, & Black Hare Press' Lockdown Sci-fi Anthology Series. “What’s that supposed to be?” Noah Allen, sleeves rolled up to his forearms and sweat beading on his forehead, dabbed little green scales onto the shop window. “Starbucks logo.” “Yeah, but what is it?” “Mermaid maybe?” He squinted at the window in the glare of the Manuxet River. “Who knows? They just pay me to show up and paint.” Noah did a lot of odd jobs around town: pressure washing houses, cleaning rooftop gutters, fixing boilers and plumbing. The Allens had been here as long as anyone. Came in the early 1800s and stuck around our crappy little oceanside town for whatever reason. “Why would anyone open a Starbucks here?” “Dunno,” Noah said, taking a rag out of his jeans pocket and scrubbing his brow. “Maybe they want to sell us coffee. What time’s the shindig start tonight?” “Seven o’clock. You gonna be there?” “For your mama? Wouldn’t miss it.” I headed down Marsh Street towards the grocery store. Innsmouth had changed in the past few years. Warehouses had been renovated into studio apartments, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean; new rustic farm-to-table restaurants popped up every week with menu offerings like smashed avocado on toast. We even got an Urban Outfitters down on Water Street, but when I went inside to check out one of the T-shirts in the window, all the cashiers stared at me like I’d done something wrong. So I left without buying anything. Stepping into Wegmans, I pulled out the grocery list my mother had prepared: plantains, chicken, flour and lemon juice for the pica pollo. And more than enough soft drinks for anyone who showed up on our doorstep. I was grabbing a six-pack of Coca Cola when I noticed him across the aisle. He was wearing a cardigan sweater with patches on the elbows, and his glasses slid down low on his nose as he examined the nutritional information on a box of ramen noodles. He was the handsomest man I’d ever seen. I followed him around the grocery store for a while, watching while he shuffled through coupons. When he got into the express lane, I slipped in right behind him. “That’ll be twenty-three dollars,” the cashier said, ringing up the man’s order. He counted the change out of his pocket. And then re-counted it. And then re-counted it again. “C’mon, man,” shouted someone from the back of the line. “We all have places to be.” “I’m really sorry.” The man checked all his other pockets for any hidden loose change. “Um, could you take off the —“ “How much do you need?” I asked, pulling out my bus fare. I could always walk home. He turned to look at me, and I wondered what he saw: round unblinking eyes with giant black pupils dotted right in the centers, dark skin with ashy patches of scales, the same thick lips as my mother. I expected him to ignore me, the way all the newcomers did, but instead, he grinned. “Seventy-five cents.” I gave him my change. His finger brushed against mine as the money passed between us. His nail was bitten down to the quick, and his cuticles were ragged; mine had tissue paper-thin webbing attaching it to its neighbor. “Thanks.” He handed the dollar to the cashier and packed his groceries into the bags he’d brought from home. “Do you live around here?” he asked, as the cashier scanned my items and took my EBT card. “A few blocks away, yeah.” “Mind if I walk you home?” His name was Russell Olmstead. He’d dropped out of Miskatonic University when the tuition bills had gotten too steep, but he still had forty thousand dollars in student loans to pay back. He’d moved to Innsmouth because the rent was cheap, and his job allowed him to work remotely. He didn’t have two cents to rub together right now, but that’d change, he told me. He was going to become something. I told him he’d be better off leaving Innsmouth then. Nothing ever happened in this shit-hole town. When we reached the Eliot Street Housing Development, he scratched the back of his neck and said, “Well, I should probably be getting back —“ I blurted out the words I’d been carrying around, heavy as my grocery bags, since we left Wegmans: “My mother’s moving next week.” “Where to?” “You wouldn’t know it. She’s having a going-away party if you want to come.” I lifted up a cluster of plantains and gave them a little shake. “Free food.” Russell glanced towards the rickety wooden pier down the street from our building. The water whipped up against the stilted legs, brown and frothy like watered-down cocoa. He couldn’t have known what was underneath those waves, but maybe he suspected. Maybe he’d also dreamed of tentacles crawling up the boardwalk and ripping street-lamps out of the cement. “Sounds great,” he finally said, stuffing his hands into his jeans pockets. “I’d love to get to know the neighborhood better.” “We’ll show you the real Innsmouth,” I smiled. But the corners of my lips were tighter than both our bank accounts. As he shuffled through the steel security door, I almost stopped him, even though I’d been the one to invite him inside. Leave! You’re not like us! But it was as if my breath had been caught in a riptide and pulled deep down into my throat; the words struggled to break the surface and then drowned. My mom came out of the kitchen, wiping off webbed fingers on her apron. “And who’s this young gentleman?” she asked, jagged teeth stretching up into a smile. I clenched my toes inside my flats. I knew we were different from the outsiders, knew they’d probably find our traditions, our appearance, our whole way of life strange. But I’d never been embarrassed of my family until that moment. And then I felt embarrassed about being embarrassed. Because why should I be? We’d been here first after all; Innsmouth was our home. If these people decided they wanted to live here, wanted to erect their Starbucks on our street corners and post photos of our harbors on Instagram, then what should that matter? We didn’t have to change for them. If anything, they should be changing for us. “Russell Olmstead,” he said, grasping her hand in his own. She nudged a chair out from the table and had a seat. Her bulging amber eyes caught the light streaming in from the windows. “You new to Innsmouth?” He nodded. “Used to be a good community,” she said. “But then the government came in. Detonated explosives out in the water, arrested most of the locals. Now what do we have?” She humph’ed and looked out the window. Russell glanced over at me with a nervous smile, not sure what to say. I shrugged. “Olmstead,” she repeated and looked him up-and-down. “You have family from around here?” “An uncle. He’s renting me his old studio for two hundred a month.” I noticed it then. The strange roundness of Russell’s eyes. As familiar as a used pencil, chewed-up and dull, in the bottom of my backpack. Maybe he wasn’t as much of an outsider as I’d first thought. “This neighborhood may not be perfect, but just between you and me—“ She leaned in closer to him, propping her scaled elbows up on the tabletop. “There’ll be worse places to be when times get tough than here with us in Innsmouth.” Russell went real quiet for a while after that, staring out the window at the churning sea. And everything that might lurk beneath its sparkling waves. V. A. Vazquez comes from New York City where she has previously worked as a theatre producer, an arts educator, and a ghostwriter for famous fashion editors (which you wouldn’t be able to tell from looking in her closet). She writes urban fantasy and specializes in stories that involve women (or men or non-binary folks) romancing monsters, preferably the slimy Lovecraftian kind. She currently lives in Scotland with her husband and their wee doggo. “No, Emilie, you can’t make me eat Cthulhu tentacles! It’s barbaric!” Mark couldn’t stop the sweat pouring out from his temples as steam rose out of the pots and the grills surrounding them. Each wooden table had a round grill indented in the center, barbecuing tentacles and thinly sliced meat, in addition to a personal steel pot boiling in front of each restaurant patron. “For once, can you shut the hell up about how I’m barbaric if I don’t eat like you?” Emilie glowered at Mark, her frown and the furrow between her immaculate brows doing nothing to spoil the smoothness of her porcelain BB cream and tinted cherry blossom lips. “You lost the bet with me. You’re going to eat some Cthulhu tentacles.” “I can’t believe people of your culture eat this crap. It’s cruel! You eat dead animals and call yourselves civilized?” Emilie’s brows rose while her dark eyes narrowed. Her long lashes stayed still, like frigid snow-frozen branches. “You’re calling me barbaric again?” “No, Emilie, not you! You’re...you’re not like the others!” “And how am I not like the others, Mark?” Emilie rested her pointed chin in a slender hand. “Explain that to me.” “Well...uh…” Mark sweated, no longer sure if it was because of the heat and steam that permeated the restaurant, or if it was because of Emilie’s sharp glare. “You’re beautiful, I’m...I’m dating you--” “And so because I have a white boyfriend, that puts me above others of my background?” snapped Emilie. “Is that it?” “That’s not what I’m saying!” “Then prove it!” Emilie pushed a plate of takoyaki balls to Mark, the golden dough glistening like freshly glazed donuts swept out of an oven. Emilie’s stare bore into Mark like knives. Eat them. Eat them, Mark. Eat them, and shove your white supremacy down your throat. Mark picked up one skewered ball, clamped a hand over his eyes, and poked out his tongue as he teetered the takoyaki ball closer. The scent of hot, sweet batter submerged his entire head. The dough shell bloomed on the tip of his tongue, warm and savory and crispy, like a hushpuppy. He sank in his teeth. The slight crunch of the golden skin gave way to the umami flavor and chewiness of the chopped tentacles enveloped in the soft, moist dough, tinged with the tang of seaweed and green onions. A new hunger surged from within him, a tidal wave of appetites flooding his nerves. He stabbed each takoyaki ball, one by one, and chewed on each impaled delicacy with the vigor of a man discovering a new obsession. All the while, Emilie watched him as she cradled her pointed chin in her scarlet-manicured fingers, her eyes fixed on him like a vulture never leaving its stare from its prize. Once Mark licked the plate clean of sharp mustard and worcester sauce, he met his girlfriend’s gaze for approval. Her eyes remained stony. “Now eat this.” Emilie pushed him a plate of live Cthulhu tentacles wriggling on the plate. Each glistening tentacle resembled living threads of oscillating jewels, marbled in a harmony of emerald green and vibrant violets. As Mark’s stomach felt as though it flipped inside-out, Emilie plucked a leg from the plate. She slurped on it like a noodle, gnawing on the thick flesh between each small suck as she stared at him. Her eyes remained unblinking. He followed her lead. He dunked one of the long appendages into a generous heaping of sesame oil before clenching his teeth around the rubbery flesh. The suctions sucked at his tongue and teeth, sticking to him, thrashing with a willingness to live. It was alive, it was fresh. He chewed and chewed, the slightly sweet sesame oil lubricating his teeth with each bite. When he swallowed, the Cthulhu tentacle slithered down his throat. He expected to choke, or even be rushed to the emergency room, as he had heard stories of grisly deaths met by those who did not take their time to thoroughly chew on Cthulhu tentacles. He took a pause to sip on iced water. Emilie plucked another swirling tendril from the plate and brought it to his lips, like a mother bird feeding its chick. Her red lips stretched into a smile as Mark chomped down on the offering. After swallowing that one, he dunked another, then two, then four Cthulhu tentacles into the glass bowl of sesame oil that Emilie kept refilling for him. He gorged on them as if sacrificing himself to drown in an ocean of steaming noodles. Each oscillating extremity filled him with warmth and gusto that he had never been raised to appreciate. Years of nibbling on limp leaves and ungarnished salads had left his taste buds barren. But here, here was life. The thrashing and squirming of Cthulhu tentacles swarming his tongue like fresh ramen, the scent of grilled meat and salted ocean flesh tingling from his nose and all the way down his spine, the warmth of steam submerging the entire restaurant, they all rang bells within his body. Bells that rang like a ceremony to welcome the resurrection of joy, of taste, of life. When he engulfed the last of the Cthulhu tentacles, he coughed. Grabbing his glass of ice water, he gulped down the cold refreshment. His jaw hung as he slammed down his drained cup. For once, Emilie bore a wide grin, her straight white teeth scintillating like knives framed by her red lips. She bit into a fresh order of takoyaki that a waiter set down in front of her, fluttering her lashes. “Not so barbaric, am I?” Delicious. Jo Wu was born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she studied Biology and Creative Writing at UC Berkeley. When writing, she can be found typing away in her Google Docs, accompanied by a Poisoned Apple mug that is constantly refilled with green tea, while blasting a mix of metal and orchestral scores. When she is not writing, she will be sewing her next costume or deadlifting her next powerlifting goal. Felix’s sandals slapped against the cobblestone path that snaked its way from the heart of Chicxulub all the way to its crumbling docks. His legs burned, as if his muscles had been doused and set ablaze. At the tip of the dock, Frederick Lamont flicked his cigarette into the still waters of the Mexican Gulf. The tall, pale professor from Miskatonic University waited with crossed arms, his fine leather shoes tapping impatiently on the plank floors. Behind him, the sky began to grow dark. Felix handed him the old tome and bent over to catch his breath. “Did anyone see you, boy?” Lamont asked. “Yes,” Felix said gasping. He stood and turned toward town. The chorus of voices began to rise in the distance like the buzzing of angry hornets. “The priest saw me take the codex.” “Damn,” Lamont said through grit teeth. “There’s no time.” He began flipping through the book’s tattered pages, biting down on his lip until a small sliver of blood trickled down his chin. “What’s so important about that book?” Felix said. “Don’t you know your own town’s history?” Lamont said as his eyes darted madly across the pages. Felix shrugged. “My mamá says that book is never to be read or discussed” “That’s why you and all your ilk will remain ignorant and subservient to people like me. Because you don’t understand the very treasures you have under your very noses.” Felix said nothing. Lamont offered the boy a quick glimpse and pursed his lips. “Oh, I suppose I can tell you a little secret,” he said smiling, tracing his fingers through lines of faded text. “Long ago, a Spanish Galleon sunk in these waters. One sailor survived, swimming into town and relaying his story to the local priest who transcribed his account into this very codex.” The drone of angry voices drew nearer, filling the streets behind them. Lamont continued. “The sailor’s account described an enormous creature that rose from the depths, bearing the tentacled face of an octopus and the body of a humanoid man. It sprouted mammoth wings from its back, which it wrathfully flapped, causing a tempest to capsize the ship.” “Like a Mayan god?” Felix asked. Lamont shook his head, his eyes never breaking away from the book. “I don’t think it’s some silly jungle myth, boy. I think we’re dealing with something real. Something alien and powerful.” A crowd of people marched down the road, their steps and shouts now a unified cacophony. Lamont began flipping through the book indiscriminately, creasing its pages and ripping away threads of stitched binding. “We stand on the very site of a large-scale global event. We are in the heart of the Chicxulub crater, where a celestial body crashed into the Earth sixty-six million years ago. It wiped out nearly all life on the planet, but I know it wasn’t just some asteroid.” The priest along with the town’s elders stepped onto the docks. They waved machetes and torches in the air like some offering to the gods. Felix felt beads of sweat accumulate on his head. “Sir, I think I’m going to get in trouble. I see my mamá coming. Can I just have my money now?” Lamont grimaced as his fingers raked across the book, flipping page after page. “The sailor made mention to the priest the beasts name, which it repeatedly bellowed out to the crew before they were destroyed. I must find its name so that I may call it. To call it is to unleash its power. To unleash its power is to in essence become a god.” He looked up at Felix, his eyes now bursting with rivers of broken blood vessels. Felix stepped back. Lamont jabbed his finger on the book, drool seeping from the corner of his mouth. “I’ve found it! By God, I’ve found it!” “Don’t proceed any further,” the priest said wrapping an arm around Felix, gently nudging him behind his own body. Felix’s mother quickly approached and pulled him toward her, her wrinkled face frowning, scolding him with a fury no words could ever convey. “You’re all too late,” Lamont said. He turned toward the Gulf’s waters and closed his eyes. “K’utulu! K’utulu! K’utulu!” The earth trembled, sending many townsfolk tumbling into the water. Felix fell, slamming his head on the planks of the dock. As he looked up, the waters began to bubble like soup in a pot. Then, a large monster sprang from the ocean, towering over the entire town like a small mountain. Lamont raised his arms in joy. “Rise Lord K’utulu. Set your eyes upon me, that I am your master.” The beast opened its eyes. Like fiery embers, they were filled with rage. Countless tentacles writhed along its mouth, as it shrieked like an angered beast. It opened leathery wings akin to those of a bat. “Mireya,” the priest said looking at Felix’s mother. “It is time, curandera.” Felix’s mother nodded and raised her arms to the heavens. She chanted hushed words in a language he couldn’t understand, as if uttering some ancient secret to the wind. Then, the sky cracked with thunder and a burst of fire lit the night. The crowd pointed to the sky and gasped. Felix turned to look. There, a feathered serpent descended from the heavens like a shooting star. “Kukulkan!” the people shouted in unison. Felix recognized the name. Kukulkan, the great Mayan god. The serpent uncoiled itself revealing its true size. Felix surmised it spanned the length of a great, winding river. Just that instant, Kukulkan spotted the water beast and hissed. K’utulu roared and clawed at the air in response. The townsfolk screamed, running back toward Chicxulub. “Come,” Felix’s mother said, “we must go.” She squeezed his hand and pulled him away from the docks. Kukulkan then closed its wings and dove downward, flying like a spear. K’utulu opened its maw to scream, but Kukulkan pierced through its heart before it made a sound. K’utulu’s eyes rolled behind its massive head, and fell backwards into the Gulf, sending up a geyser of water into the air. The shockwave rolled through the docks, splintering the wood in a mighty explosion that cast Lamont into the depths of the sea, the codex alongside him. Kukulkan shot forth from the water and flew back into the heavens, vanishing into the darkness of the night. After a moment the waves began to sway gently, until they became still and quiet filled Chicxulub once more. The townsfolk gazed thankfully upon the sky one last time and turned back home. Felix’s mother placed a soft hand on his shoulder as she led him back to town. “There are secrets, mijo” she said to him at last, “that have more value locked away in the depths of our hearts, than do all the riches in the world secured in our palms.” Felix held her hand and nodded. It would be a lesson he knew he would never forget. Pedro Iniguez lives in Eagle Rock, California, a quiet community in Northeast Los Angeles. He spends most of his time reading, writing, and painting. His work can be found in various magazines and anthologies such as: Space and Time Magazine, Crossed Genres, Dig Two Graves, and Writers of Mystery and Imagination. His novel Control Theory, and his collection Synthetic Dawns & Crimson Dusks are now available. He can be found online at: pedroiniguezauthor.com They oozed through the door of the Shade Inn, degenerate hordes with their coral shirts and adumbrations of learning. The patrons of a village bar might not drink more than a dram and could walk home. These students, given the chance, would drink themselves into states of madness, and in those states repeat the darkest patterns of half-ape savagery, shouting and singing along the lanes and thoroughfares. On the bus into town the girl with the red cap and black jacket and stressed shorts captured a pair of men who sat outside the post office, dour, elongated-faced men of Aseneith. She turned her cell to Lachlan Whatley and Jacob Wu and asked for commentary. “Do you think they’re brothers?” Whatley said. “The locals have that look of too few families living too long in one place.” She laughed. “That’s great.” Her smile sunk when she tried to post the video. Her bewilderment rippled through the chartered bus as students checked texts and tried to post photos. They could imagine losing connectivity here and there along their rustic route. In a town the experience challenged comprehension. Most of the buildings on Main Street were front-gabled, with flat façades suggesting second storeys that could only have consisted of the attics. The result was that Aseneith recalled an old west movie town made from brick. On the far side of the crossroads stood the hip-roofed, buff-bricked building which housed the Shade Inn. The upper floors seemed closed, the windows covered with faded curtains and, in some instances, boards. The heavy timber door, either the original or an antique added for historic character, had been painted sea-green and featured decorative iron straps like abstracted representations of tentacled invertebrates that stretched across each door. Black hurricane-style lanterns hung on either side; above the windows was carved a weathered, stylized face with tendrils that might have been whiskers and hair. Cater-cornered stood a church lacking clear markers of denomination. The bus parked and disgorged its riders, who with smug infectious smiles passed through the viridescent doorway. The few regulars within were the same type as they’d seen out the bus windows, heads like Easter Island statuary and ratfish eyes. Jacob Wu shuddered. At one time, the Wild Pig Tour had taken place the eve of Superbowl Sunday, always targeting some small town with a single licensed establishment. It created some ill will but, since the students drank the bar dry, the owner could hardly complain of lost revenue. A disastrous foray to a small town some years earlier engendered a fight with local boys and brought the campus unseemly publicity. People unaware of the tradition, benefactors and parents and quite a few students, could now disapprove. Nearby towns grew apprehensive about falling prey to this particular prank. Organizers had to look further afield for communities that remained unwary or, alternatively, gave a damn. Some places even welcomed them, so long as fisticuffs and public urination were kept to a minimum. And the indecorous tradition increasingly did not raise sufficient crowds, students willing to trudge through January snow or risk becoming blizzard-bound in some obscure town. Gradually, the Tour became untethered from a fixed date. Organizers would find some backwater hosting a wedding the next day or running a homespun parade. The Wild Pig would descend upon that place, drain the local watering hole, and depart. Inquisitive Jacob Wu had unearthed an obscure online reference to a one-day Harvest Festival held the final Saturday of September, two hours away. He showed it to Lachlan Whatley, a Wild Pig organizer. A Google search revealed the required single licensed establishment, a former inn that had become a restaurant and pub, owned by one Mustapha Al-Aziz. “Syrian refugee, maybe?” asked Whatley. “Like how back in the day every small town had this one Chinese restaurant. Because--” “Obligatory Token Minority.” “Careful, dude. I’ll kick your ass with, like, Ancient Chinese Martial Arts.” “Your mad Ninja skillz?” “Ninjas are Japanese,” Wu said, affecting a comic pedant’s voice, but sounding unoffended. “Excellent find, bro. We gotta move on this.” Two weeks later they encountered Mustapha, who stood behind the bar, a swarthy man with a black mustache and a polo shirt. He spoke with a discernable accent. Mustapha’s waitress had a curvaceous body topped by a variation of the regulars’ curious, elongated features. Her skin, seen close, had an unnatural jaundiced shade. Whatley turned to the girl who’d recorded them, taking a closer look at her cap. “Cincinnati Reds.” “You thought it was some other red hat? Well, I could see wearing a MAGA hat around campus to trigger all the Snowflake Majors.” Whatley moved closer and they tipped glasses. “I know he’s a clown, but by God I love the boy.” Her roommate, a redhaired girl named Haisley, rolled blue-green eyes and took the vacated seat near Jacob Wu. Time passed for him in a haze of intoxicants and Haisley. At some hour, while she was using the washroom, he grew aware of a pair of stout students arguing with the proprietor. “You got more in the back. Bring it out.” They were square-jawed and block-built, and loomed over Mustapha. “No rough stuff. Or I call the cops.” The local men stirred. “Call. There are, what, two cops covering this part of the county? C’mon. How much would you serve at your harvest festival?” Mustapha smiled enigmatically. “You should leave now,” he said. Wu blinked and looked about. He recalled their drive down Main Street. The inn, like the rest of the town, lacked any signs of an imminent Harvest Festival. He became aware of local men crowding in, and looked back to see shadowy figures lurking in the windows. Frat brothers and drunk intellectuals stood off against ochre-skinned men. Mustapha again urged the students to leave peacefully. Above the din of conflict Wu heard a knocking. He turned his face upward to the ceiling. He could hear the stepping and creaking like multifarious feet in the vacant upper rooms, accompanied by a dragging noise. A line of dark fluid, visible by the bar’s light, dripped through the boards. More men and some women entered through the great doorway. Some teenage boys he saw, too, mudcat-faced with bulbous eyes and mouths distorted in a way he could not clearly discern. Haisley, returning from the washroom, nearly walked into one of these and gape-eyed, she gasped. The fire exit, he knew, was near the washroom. He moved on unsteady legs past inhuman faces and took her hand and they exited, setting off the scream of an alarm. Behind the parking lot a diseased tree twisted against the barley moon. He looked up and she followed his gaze. Lights flickered in the upper level and something moved in the dark small hours of the Harvest morning. The nighttime spun around them and people gathered on the street, the Aseneith adults and children with catfish faces. She bolted and he lost her as he tried to follow through shadows and down rural roads and into mad corners of his mind. ### Jacob Wu awoke from tenebrous dreams into lingering inebriation and found himself on the floor of a rustic backroom, covered in old blankets. He saw the little girl watching him and bolted upright. She ran from the room. He’d seen her face clearly. Her mouth sported silurid barbels. Mustapha Aziz and a woman of the Aseneith type entered as Wu searched for his clothing and cell. “Are you all right?” Mustapha sat on the solitary chair. “You had much to drink.” “Where…?” “My house. We’ve taken in those of you we could find. Most made the bus. The driver returned late.” The furnishings were weathered, but the clock on the desk looked parcel-new. It read 8:57. “Your friends grew discourteous, just as our harvest was to begin. Some panicked.” “We… There were so many of you.” He shrugged. “Your friends come to us and see faces they do not recognize and they act violated. Surely our anger is not something I need to explain to you. Any other time, we would have no big deal. We thought you’d leave. Harvest is very important to her people. They make a sacrifice each year.” “Haisley? Whatley? My friends--” He shrugged. “As I said, we’re looking after those few who did not find the bus when it returned.” Wu tensed. “Sacrifice?” “What?” Mustapha laughed, outrageously. “No, they slay some sheep, some chickens. My wife’s people found refuge here. So you saw… In the upper windows?” Wu nodded. “It sleeps there. Awakes at harvest. We require you say nothing.” “It’s possible some of the others saw….” “Possible. But they were drunk. Her god is now in its temple. Locals only.” His wife brought in a glass of water. “I’m cooking oatmeal, if you think you can keep it down.” The barbel-faced child, peaking from behind, giggled softly. Mustapha stroked his moustache. “Your friends, yes.” He arose. “One imagines they see many monsters.” JD DeLuzio lives midway between Detroit and Toronto with his wife. He has written several short stories, numerous reviews and articles, and one collection of fiction. He has also workshopped original theatrical productions with youth. He frequently runs panels at SF, pop culture, and literary events. His short story, "The Rapture of Baatoon Hayes" appeared in the recent Brain Lag anthology, The Light Between Stars, and his novel, The Con, will be released in November of 2020. |

The Were-TravelerCurrent Issue: Archives |

Photo used under Creative Commons from deborah's perspective

RSS Feed

RSS Feed